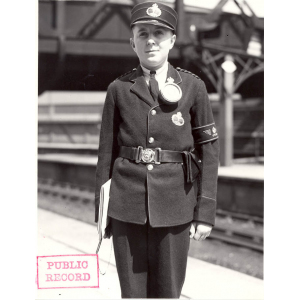

Boy messenger at Paddington Station, 1935

© Royal Mail Group Ltd [1935], courtesy of The Postal Museum, POST 118/426

In 1936 the Postmaster-General wrote in an article entitled ‘Making an A1 Nation’ that ‘the Post Office may indeed fairly claim…that it has in its employment a healthy and happy body of boys of whose conduct and appearance it may justly be proud’.

The term ‘A 1’ was a military category meaning ‘fully fit’ and its use in the interwar years reflected concerns about ensuring the health and fitness of future generations after the First World War.[1] The boy messengers employed by the Post Office were not just future homeowners and breadwinners, they were also potentially future sorters and postmen, and soldiers as well.[2] Therefore, their fitness and health, as well as their ‘conduct and appearance’, were of major importance to the Post Office and to society as a whole.

To provide evidence of the boy’s’ health, the Postmaster-General drew on earlier articles by the Post Office’s Chief Medical Officer on “The Physique of Young Londoners” and ‘the problems of growth’. This work used measurements of two hundred boy messengers aged sixteen between 1929 and 1931 with the same number of boys of the same age between 1905 and 1908. It then compared the rates of growth of one hundred Post Office boys working in London with one hundred public school boys living in the country.

The research showed that in the earlier period, the average height and weight of the two hundred boy messengers was 5 ft. 5 in. and 8 st. 3 lbs respectively whereas in the later years these figures had risen to 5 ft. 6 ½ in. and 9 st. 5 lbs. The Chief Medical Officer celebrated the fact that on average boy messengers in the later period had become taller and heavier than their predecessors.

In addition to the height and weight of boy messengers as an indicator of healthy bodies, the Chief Medical Officer was also interested in the rates of growth of the boy messengers in London as indicated by their heights and weights at the ages of 14, 16 and 18. Anxiety about the impacts of urban life on young bodies, and fears of urban degeneration, had been voiced since the late nineteenth-century and these were reflected in the anthropometric comparisons made between boy messengers in London and public schoolboys in the country.

The heights and weights of one hundred boy messengers and one hundred schoolboys ‘at a well-known public school in the country’, who ‘were living and being educated under usual public school conditions’ were measured over a four year period, between the ages of 14 and 18, and compared, as shown in accompanying tables.

Table 1

| Post Office Boys Messengers (London) | Age: 14 | Age: 16 | Age: 18 |

| Ht. | 5 ft. 2 in. | 5 ft. 7 in. | 5 ft. 8 ½ in. |

| Wt. | 7 st. 3 lb. | 9 st. 2 lb. | 9 st. 11 ½ lb. |

Table 2

| Public School Boys (Country) | Age: 14 | Age: 16 | Age: 18 |

| Ht. | 5 ft. 2 in. | 5 ft. 7 in. | 5 ft. 9 ½ in. |

| Wt. | 7 st. | 9 st. | 10 st. 4 Ib. |

The data in Tables 1 and 2 show that average increase in height and weight of Post Office messengers between 14 and 16 was practically the same as for public school boys. However, the Chief Medical Officer stressed how ‘between 16 and 18… the public school forged ahead to the extent to 1 inch in average height and 6 ½ lb. in average weight’.

An explanation of this was offered: ‘this may possibly be due to the continuance at the public school of a regular regime of work, play, and hours of sleep, less likely to be observed by working boys, over 16, living under metropolitan conditions.’. In contrast to life in the country at a public school, the boy messengers in London performed 48-hour working weeks, inclusive of six hours of schooling, although they did have access to ‘institutional facilities for games and gymnastic activities out of working hours.’. The Chief Medical Officer concluded that ‘it would appear that a public school life in the country possesses a definite physical advantage…in the case of the boys after the age of 16’. More optimistically, the article also noted ‘that the average London boys…of to-day are considerably the physical superiors of their counterparts in the last generation’.

Measuring health was a concern in the early twentieth century as part of a growing preoccupation with national efficiency and the wider health of the nation. Small scale enquiries, such as the ones undertaken by the Post Office relating to boy messengers, despite not having the statistical robustness of larger studies, tapped into these concerns about urban life and Britain’s ability to continue to perform its imperial role on the wider global stage. The physical stature of boy messengers had improved over time, which gave grounds for optimism, but disquiet remained about the impact of work on youthful bodies, especially in large urban centres.

Natasha Preger

[1] For more on this, see Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Managing the Body: Beauty, Health, and Fitness in Britain 1880 – 1939 (Oxford, 2010), particularly Chapter 4.

[2] Boy Messengers could express a desire to join the Army or the Navy and remain as Messengers until old enough to enlist. In some cases, these Boy Messengers could also return to work for the Post Office once their Army or Navy services expired.