‘He begins his week’s work at four o’clock on Sunday afternoon; he ends it at half-past ten on Sunday morning; and at any time during that long week he is liable for instant service, and has only five and a half hours’ undisturbed rest…that is the only respite he is sure of—just enough, as it were, to go to church and digest the Sunday’s dinner.’ (p. 70)

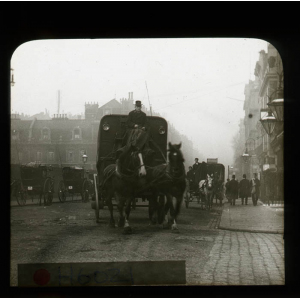

While the above quote could just have easily been a description of the conditions of the Victorian postman, it actually refers to that of the Post Office horse. The description comes from William John Gordon’s The Horse-World of London (1893), who was the author of other such works as How London Lives and The Story of Our Railways’. Despite the increasing presence of motorised vehicles in turn of the century London, Gordon’s work reveals the continued ubiquity of the horse in the city. The range of equine duties Gordon covered was extensive. He wrote that, ‘in the horse-world of London, the highest circle, the most exclusive set’ was that of ‘the Queen’s horse’ (91) but that it was the omnibuses that were ‘the greatest users of living horse power in London’ (10). Nevertheless, it was ‘the mail horse’ that was ‘the least conspicuous of draught animals’, being as they were overshadowed by the scarlet of the mail cart which accompanied them (69). Seemingly, even though Post Office horses worked such tiring hours, their toil went unnoticed. Admittedly, Gordon extended this conclusion to the human postal worker as well.

From reading Gordon’s reflections on Post Office horses, it might appear that they were overworked, unrested and underappreciated. To keep up with the mail, the Post Office horse was in many ways ‘always at work’, ‘what with ‘mail inwards’ in the morning, ‘mails interchangeable’ during the day, and ‘mails outwards’ at night’ (70). Horses also had to work with the ‘‘foreign mail’s arriving before their time at all hours of the day and night’, in addition to the length of the working week (70). The problems with this did not go unnoticed by Gordon. He even framed the Post Office horse as responding to his workload in a characteristically human fashion, with ‘quite enough to employ and worry him’ (70). This is then underscored with the note that, compared with the tram horses who were worked for four years and the omnibus horses who were worked for five, the mail horse had to wait six years on average to be released from service. The lot of the Post Office horse does not appear to have been an enviable one.

Overall, however, Gordon’s assessment of the life of a Post Office horse is positive. Although they began work early, finished late, and had to keep up with the hustle and bustle of the nineteenth-century Post Office, Gordon stressed that it was not often that mail horses were sick. For the most part, Gordon attributes this to the ways in which the Post Office horse was cared for. He was looked after and checked up on by keepers at every stage of his working life, at the railway stations and at the various stables he was required to move between. The horses’ living quarters too were rigorously managed, regularly disinfected and scrupulously whitewashed. Such commitments help to explain as well why the Post Office horse cost more than his omnibus competitors. But, as Gordon noted, the high costs proved worthwhile. Regardless of his workload, everything was done to keep the Post Office horse in good health.

Records from The Postal Museum illustrate that Gordon was not far wrong in this regard. A highlight from their collection is a note from 1898, which stated that ‘Mr T. C. Poppleton’s horse of the Post Office is suffering from sore shoulders’ rendering him unable to perform his regular duties. As a result, the horse was granted sick leave. Although the horses were not employed by the Post Office and were provided by contractors, they were still entitled sick leave. The horses’ diet was also of great importance to the Post office. For instance, the quantity of forage was calculated and documented in detail and depended on the average amount of work performed per horse per day. Included in this as well was an allowance for horses who had worked for longer. If a horse had worked longer than five hours in a day he was granted an extra 2lbs of corn. It was even noted that, if underfed, hard work could not be expected of the horses and that — in extreme cases of hunger –the Post Office horse was known to resort to eating his own bedding. Gordon also acknowledged the importance of diet (‘the Post Office horse is fed well – indeed, if he were not, he could not stand the work’, 71).It is noteworthy that it was so fastidiously overseen by the Post Office management.

It is true that Post Office horses were not always seen in a positive light. They could be unpredictable, resulting in an association with inefficiency and risk in the workplace. In 1909 there was even an inquiry into accidents involving mounted postmen and Post Office horses and if they qualified for compensation. This might as well add to our understanding of why they were so carefully managed. It’s intriguing to think about how different postal workers worked together and how they saw each other, across occupational (and interspecies) boundaries.

What is immediately clear, however, is that the Post Office horse was integral to the successful running of the nineteenth-century Post Office. Postal workers were the ones who delivered and sorted the mail, but horses were the intermediaries in carrying it from place to place. They may have passed unnoticed alongside their human colleagues, but the service they facilitated did not.

Natasha Preger