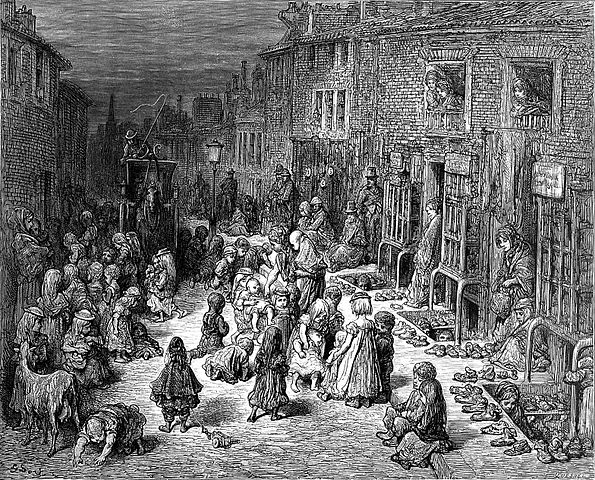

Dudley Street, Seven Dials Gustave Doré, 1872. Source: Wellcome Images, http://catalogue.wellcomelibrary.org/record=b45, Photo number: L0000881. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Few have heard of the C.I.B. (Confidential Inquiry Branch), the Post Office’s secret service department whose function it was to bring dishonest Post Office employees to justice. The C.I.B. grew in strength from 1858 when four Travelling Officers, accompanied by two Police Constables, were put in charge of investigations. However, why did the Post Office — that had for long fashioned itself as a benevolent employer — feel the need to keep such a close eye on its workers? To try and answer this question, this blog will explore what a turn to postal crime could tell us about the welfare of London Post Office workers.

Using material from The Old Bailey Online, I’ve spent the last month as a King’s Undergraduate Research Fellow on the Addressing Health project looking at court transcripts and other materials to try and understand the conditions of London postal workers. In some ways, Post Office employees enjoyed rare benefits not afforded to other types of Victorian workers. Few employers offered their workers free medical provision at a time when only the middle classes could afford access to the services of a qualified doctor. The Post Office did, establishing a free Medical Service for ‘established’ workers who earned less than £150 a year in 1855 and providing generous amounts of sick pay.

As the size of the workforce grew (from 20,000 in 1850 to 167,000 in 1900)[1], so too did worker discontent. Why was this? Claims made by the Post Office that they provided workers with earnings that went ‘way beyond the living wage’ proved to be illusory. [2] In the 1880s there were some employees still in receipt of less than eighteen shillings a week, which was below the minimum income that the social investigator, Charles Booth, stated was necessary to remain above the poverty line. By 1904, most postal workers considered twenty four shillings a week to be the ‘moral minimum rate for unskilled labour’, and complained bitterly that their current wages were condemning them to a ‘slum dweller’s life’[3] even when topped up with overtime pay. This combination of a demoralised workforce, depressed wages, and poor working conditions underpinned an increase in postal crime in the 1880s and 1890s in particular.

Of the 833 postal employees tried in the Old Bailey from 1859 – 1908 for mail theft, 24.6% were tried in the 1880s, followed by 27.9% in the 1890s and 25% in the 1900s. As crime in the Post Office rose, officials began to rely on ingenuous methods to catch the perpetrators. Besides from keeping employees under surveillance, they also directed test letters to be sent to empty houses or fictitious addresses.

The Old Bailey court transcripts provided limited insight into the health of London postal workers. However, when workers were given the opportunity to speak in their own defence we are sometimes given a glimpse into how difficult working conditions and low pay may have led to an increase in crime. In 1867, William Thomas Cox, of Ashby Street, Hackney, pleaded guilty to stealing a test letter whilst employed as a letter carrier. Despite pleading with the court to be given another chance to regain his character claiming that ‘I have a wife and three young children, and one is dying of heart disease’ he was sentenced to five years penal servitude. It is telling that workers who provided evidence to select committees investigating Post Office wages, complained bitterly on how a doctor’s bill for their family, who were not covered by the Post Office Medical Service, could ‘probably take twelve months of self-denying economy to clear off,’ even though most of them lived ‘hand to mouth.’[4] Perhaps it was the financial pressures caused by his child’s illness that motivated Cox to steal.

When Henry Fawcett was appointed Postmaster General in 1880, his chief concern was how the Post Office should respond to workers’ demands over their rights to form trade unions and over pay and conditions. Previous attempts by postal workers to negotiate their low wages and poor working conditions had ended in two failed strikes that took place in 1858 and 1871, resulting in the dismissal of over two hundred employees. In January 1881, for the first time, representatives from all main offices were invited to a national conference to air their grievances. Five months later Fawcett introduced a series of labour reforms known as The Fawcett Scheme that led to some improvement in pay scales. However, his sudden death in 1884 meant the scheme was never fully realized and the Post Office continued to adopt a hostile attitude to union activity.

However, as discontent grew so did workplace crime. The Post Office concerned itself with finding new ‘ways of keeping their employees honest’[5] (such as through test letters), that could have exacerbated the mental and financial pressures many workers were already experiencing. In turn, the juries – no longer oblivious to the poor working conditions of the Post Office – began to adopt a more lenient attitude towards mail theft. This is reflected in the changes to the length of average sentences that judges handed down to defendants in the Old Bailey. From 1859-69, the average sentence was around 49 months, changing to 43.5 from 1870-79, to 34.5 between 1880-89 and finally to 12.6 between 1890 – 1908.

My research has allowed me to begin to unravel the link between the Post Office’s attitudes and treatment of its workers and the rise in postal crime. Post Office employees were comparatively well educated – they had to pass a literacy test and Civil Service exam to be taken on – and so had a sense of respectability relating to their status in society. Their pay, however, lagged behind and so their economic status failed to reflect their social standing as an employee of the state. For an increasing number, this disjuncture proved difficult to bridge, resulting in many turning to crime to supplement their wages.

Saskia Alais

Endnotes

[1] Royal Mail Group, ‘Amassing a huge workforce,’ http://500years.royalmailgroup.com/gallery/amassing-a-huge-workforce/.

[2] Committee on Post Office Wages. Minutes of evidence taken before the committee appointed to enquire into Post Office wages, with summary, appendices and indexes. Part II. – Minutes of evidence. Parliament. 1904. (Cd. 2171 Vol. 33).

[3] Committee on Post Office Wages. Minutes of evidence taken before the committee appointed to enquire into Post Office wages, op. cit, 1904.

[4] Committee on Post Office Wages. Minutes of evidence taken before the committee appointed to enquire into Post Office wages, op. cit, 1904.

[5] Adam, Hargrave Lee. The story of crime: from the cradle to the grave (UK: Ulan Press, 2012), 264.