Today marks the International Day of Families. As the UN points out at times of crisis, it can be ‘families who bear the brunt of the crisis, sheltering their members from harm… at the same time, continuing their work responsibilities’. For many, family has never felt more important, and to mark this special day we wanted to take the opportunity to trace how Victorian postal workers and their families supported one another during times of ill-health.

For the vast numbers of letter-carriers and rural messengers, later known as postmen, pay was low and conditions were tough, leading many postmen to retire due to ill-health. Many, however, put off retirement for as long as they could: you could only obtain a full pension after ten years work and the amount granted was calculated on a fraction of sixtieths of their salary, with small increments based on length of service. Due to this there was a clear financial incentive for all workers to continue in employment for as long as possible. This would have been even more pressing for those at the bottom of the pay scale.

Within the pension records of over 1200 employees that we’ve gathered so far, we’ve uncovered two extraordinary examples of how important sons could be to ensuring wages were still paid and full pensions achieved for some of the lowest paid.

Spilsby Station, c. 1890. Source: Wikipedia

The first is the case of a rural messenger based in Spilsby, Lincolnshire. William Wales retired in 1861 due to a disease of the lungs. His pension application noted that he had stopped work in May 1861 but had been ‘assisted by his son’ since August 1860. It was not uncommon for employees retiring due to ill-health to have been off work for a year before applying for their pension. During that year part of the worker’s wage would contribute to paying for a substitute and that year off sick would not be included within the pension calculation. In William’s case this was not necessary as his son Edward helped him with his round. Assistance that secured a full wage for the household and ensured William reached the important ten-year service milestone that guaranteed a pension. In August 1861 William Wales was granted an annual pension of £6 1s 8d, exactly ten sixtieths of his salary, an official acknowledgment of his work and acceptance that the father and son’s work combined work equated to one wage.

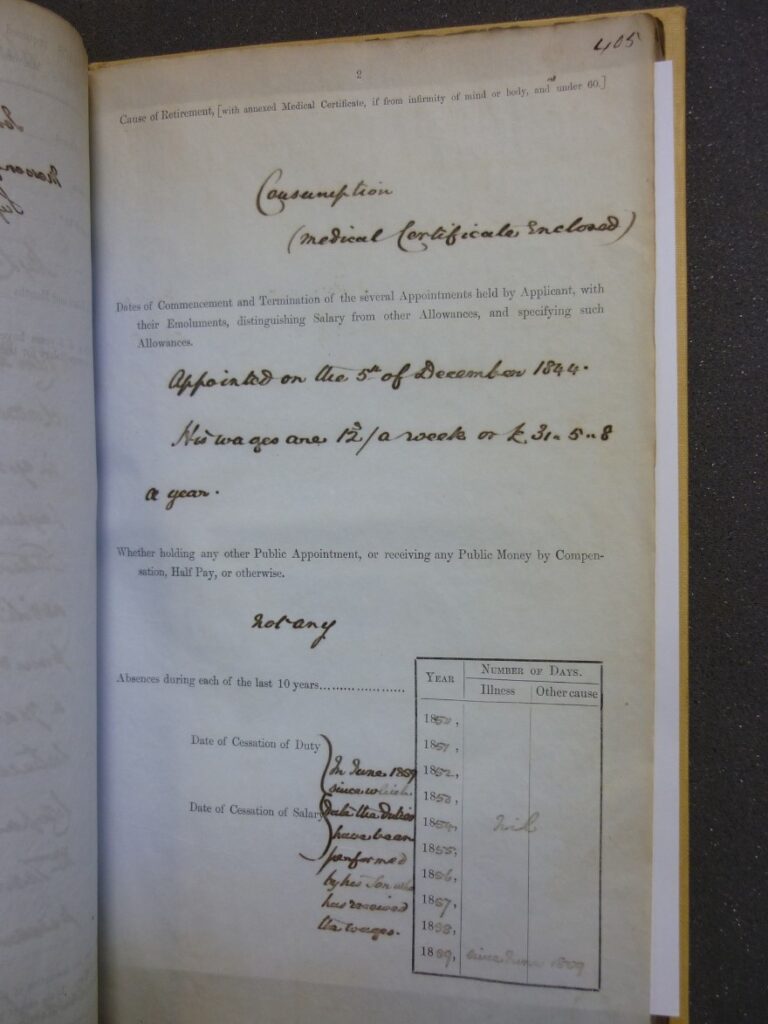

John Trerise’s pension record noting his son has performed his duties. Source: Postal Museum Archive POST 1/110

A second example is that of John Trerise, a letter carrier based in the Lizard area of Cornwall. In August 1861 John applied for a pension as he was suffering from consumption. His application noted he had stopped work in June 1859 but that his son Joseph had stepped in. As with William, both father and son were treated effectively as ‘one’ worker’, and so John was granted a full pension. Joseph, was eventually officially employed by the Post Office as a letter-carrier between Mullion and the Lizard in 1863, but this was most certainly the same walk he had been doing since 1859.

These may be only two examples out of 1200, but they are significant. They show how the Post Office and the Treasury were willing to accept sources of familial labour as a substitute for established labour. It is quite possible that William and John’s sons were part of the large unestablished postal workforce, and as such were considered temporary employees without access to any benefits. The census returns for 1861 list William son Edward Wales as sub-post office messenger and Joseph Trerise as rural post messenger. There is only evidence of Joseph becoming a permanent established employee, however. Secondly, it is proof of a practice that was probably a lot more widespread, especially in rural areas. Familial labour would normally be absent from the official record. This was clearly an arrangement that benefitted everyone, it both ensured the domestic household benefited from a continuation of income, and it guaranteed the Post Office a continuation of service.

I’m fascinated by the history of postal families, and have writen about it before, but there is much more work to do. As a project we hope to find out a lot more about how postal workers managed ill health at work, and also the role family had to play and we’d love your help. Please contact us if you’d like to help with the project from transcribing documents to sharing your own research into your postal family history or local history. Reach us at [email protected] to get in touch.

Kathleen McIlvenna: @kathleenmcil

15 May 2020