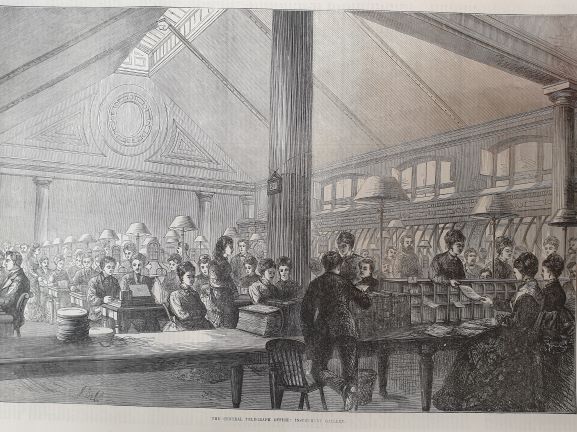

The Central Telegraph Office, General Post Office, London, 1874

Source: Illustrated London News, 12 December 1874

“The practical absurdity of directing a female medical inspector to inquire into and report upon the minute of every ailment which may temporarily incapacitate the rougher sex from a performance of their duties in the Telegraph department.”[1]

This excerpt from The Globe newspaper in November 1882 voices the ‘concern’s of medical men following the decision of Postmaster General Henry Fawcett to appoint Dr Edith Shove as female medic at the General Post Office (GPO) in London. Following the death of Chief Medical Officer (CMO), Dr Waller Augustus Lewis in September 1882, the vacant CMO position was filled by Lewis’s successor George Carrick Steet. However, the Post Office had experienced an influx in women workers after they launched their Telegraph service in 1870.[2] Women were also employed as learners, sorters and clerks, with 41.6% of clerical positions being filled by women in 1900.[3] Dr Edith Shove was therefore appointed to examine and manage the health and wellbeing of the rising numbers of postal women.

Dr Shove began her career as a licentiate of medicine and midwifery at Queen’s College Ireland, before obtaining her MB from the University of London in 1882 as one of the first graduates of the London School of Medicine for Women (LSMW).[4]. She was a highly regarded demonstrator in anatomy at the LSMW, which was unusual at a time when women’s involvement in dissection was discouraged. [5] In spite of her professional achievements and medical experience, the decision to appoint Dr Shove as medical officer to the GPO was deemed a risky experiment.[6] This was largely due to the common nineteenth-century belief that the field of medicine was a male domain. However, medical women fought hard for their education, and Edith notably surpassed all other candidates during her preliminary examinations for the Apothecaries Hall.[7]

The appointment of Dr Shove was depicted as solely a political act in publications such as The Lancet and the British Medical Journal. His decision was seen as a ‘stretch of power’, and he was criticized for using his position of authority to aid in the emancipation of women.[8] Indeed, Fawcett was a staunch supporter of women’s rights, and his marriage to suffragist Millicent Garrett Fawcett was also believed to have influenced his decision to appoint a woman doctor to the GPO.[9] The Postmaster General and Dr Shove were also connected by their association with Dr Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. Edith was a protégé of Elizabeth’s at the LSMW, and it is plausible that Dr Garrett Anderson and her sister Millicent recommended Edith to the Postmaster General.[10] Fawcett justified his appointment of Dr Shove by highlighting the increase in women being employed by the Post Office, mainly as clerks and telegraphists. The number of women working in the Post Office had increased steadily since their launch of the telegraph service in 1870. By 1900, around 41.6% of clerical posts were occupied by women. Fawcett believed that these women were better attended to by ‘one of their own kind’.[11] However, this was challenged by disapproving medical men, who argued that Post Office staff should not be compelled to take medical advice from a ‘she-doctor’ who was not capable of treating male workers.[12] Since Edith was only appointed to attend women workers, her opponents asserted that it was absurd to select a woman instead of a man, who would be available ‘for all hands’.[13] These responses to the appointment of Dr Shove shed some light on the competitive and often hostile nature of the British medical profession.

Investigating the lives and careers of medical officers such as Edith Shove will be a key component of my PhD, which focuses on the professional lives of Victorian and Edwardian medical officers who held Post Office appointments. My research investigates how the duties, contributions and professional interests of Post Office Medics shaped and influenced their patterns of diagnosis and advice.

This deep dive into the lives of medical professionals is what drew me to the Addressing Health project. In my previous studies at undergraduate and masters level, I enjoyed investigating patient and practitioner encounters, with particular focus on the LGBT community. My undergraduate dissertation explored ‘conversion therapy’ in twentieth-century Britain. Through this study I highlighted how medical attitudes towards homosexuality were a key factor in individuals seeking out ‘treatment’. My MSc thesis also involved a study of the British medical profession, with emphasis on the exceedingly varied attitudes towards intrauterine devices (IUDs). This study also acted as the first in-depth examination of the Dalkon Shield and its reception in the UK. My research showed that there was a great deal of interprofessional conflict surrounding the Shield device, which had implications for the device users who sought advice on this method of birth-control.[14]

I look forward to investigating the collaborations and conflicts amongst Post Office medical officers. This should provide us with fascinating insight into how medical careers have influenced sick-leave, superannuation, and occupational health. Perhaps it will reveal whether every doctor really does believe that their pills are best.

Holly Marley

[1] The Postal Museum, ‘Newspaper Cutting’, POST 111/20, “A New Doctor in the Post Office”, The Globe (1882)

[2] E. Jordan, The Women’s Movement and Women’s Employment in Nineteenth Century Britain (London: Taylor and Francis, 2002), p.181

[3] M. Crowley, ‘Inequality’ and ‘value’ reconsidered? the employment of post office women, 1910-1922’, Business History 58:7 (2016), p.991

[4] M.A Scharlieb, ‘Dr Edith Shove MB Obituary’, British Medical Journal, 2:3957, (1929). Shove and Scharlieb graduated together from the LSMW.

[5] L. Kelly, ‘Fascinating scalpel-wielders and fair dissectors”: women’s experience of Irish medical education, c. 1880s-1920s’, Medical History, 54(4) (2010)

[6]‘A New Doctor in the Post Office’

[7] Sunderland Daily Echo, April 28 1874

[8] ‘The Appointment of Miss Shove MB to the Post Office’, The Lancet, 121:3107, (1883)

[9] For more on Millicent Garrett Fawcett and the PO, see https://postalheritage.wordpress.com/tag/fawcett-society/

[10] D. Rubinstein, A Different World for Women: The Life of Millicent Garrett Fawcett (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1991), p.59. Wellcome Library, SA/MWF/C/62, ‘Women Medical Officer to the Post Office, 1883’

[11] ‘A New Doctor in the Post Office’

[12] ‘The Appointment of Miss Shove’, The Lancet. Meta Zimmeck. ‘The “New Woman” in the Machinery of Government: A Spanner in the Works?’ in Roy Macleod’s Government and Expertise: Specialists, Administrators and Professionals, 1860-1919 (United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2003)

[13] Ibid, Meta Zimmeck. ‘The “New Woman”

[14] For more on the Dalkon Shield see M. Marsh and W.Ronner. The Fertility Doctor: John Rock and the Reproductive Revolution (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2008), C. Takeshita, The Global Biopolitics of the IUD: How Science Constructs Contraceptive Users and Women’s Bodies (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2012)